“Vedere l’invisibile”: imparare l’arte delle note. Recensione della collana di David Nafrìa.

Abbiamo letto i 5 volumi del fondatore di TheRallyDriver.com: ecco cosa ne pensiamo

Diciamo la verità: siamo sempre affascinati dagli onboard (o cameracar come vogliamo chiamarli) e dai loro suoni. Non tolleriamo che della musica copra rumore del motore, dei sassi che graffiano la sottoscocca e la voce del navigatore. Dobbiamo sentirci rapiti dalla situazione, come se fossimo legati al rollbar nel bagagliaio.

Quella pioggia di parole, ritmata in sintonia con la strada che avanza per molti è pura magia: servono anni di pratica e talvolta qualche corso per raggiungere i livelli di Ingrassia, Gilsoul, Martin, …

Sul mercato sono apparse alcune app come RallyPacenotes che hanno avvicinato alla portata di tutti il metodo “oggettivo” nel prendere le note: questo concetto è alla base del lavoro di David Nafrìa Mitjans e della sua collana “To see the invisible” (“Ver lo invisible” in lingua originale spagnola).

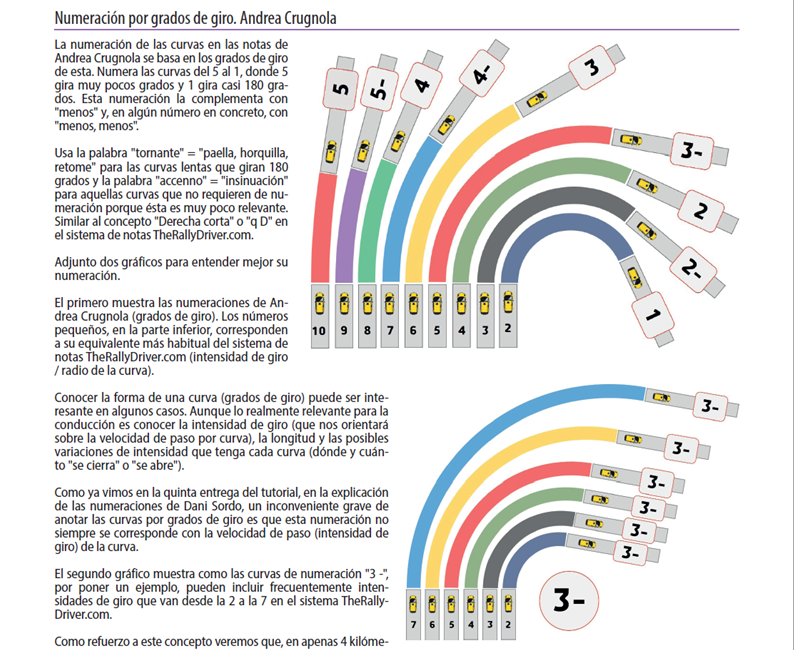

Il catalano di Barcellona classe ’71, inizia proprio come naviga nell’89: sul sedile di sinistra dal ’91, collezionerà molte vittorie in trofei monomarca spagnoli sino a diventare ufficiale Peugeot Spagna nel 2003. Tra gli acuti di carriera, il podio al Rally Catalunya nel Mondiale Produzione del 1997. Dal 2014 si dedica a corsi di note one-to-one del suo metodo, TheRallyDriver.com.

La collana è in vendita su Amazon da gennaio in lingua cantabrica ed anglosassone: si presenta con 5 volumi con copertina lucida flessibile 20.32 x 0.71 x 25.4 cm di circa 100 pagine l’uno, al prezzo di una ventina di euro cadauno.

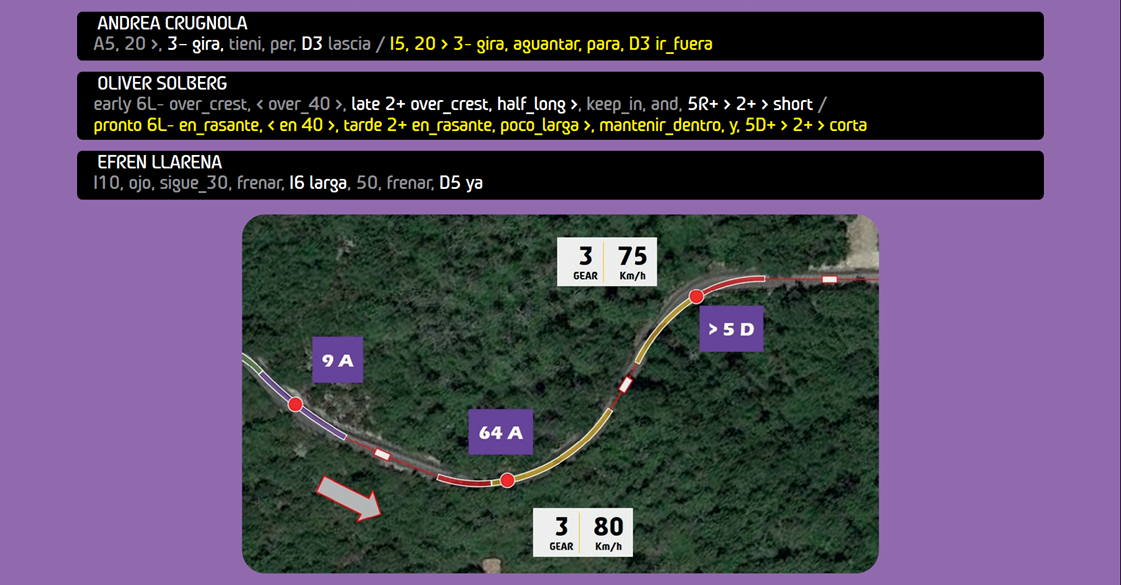

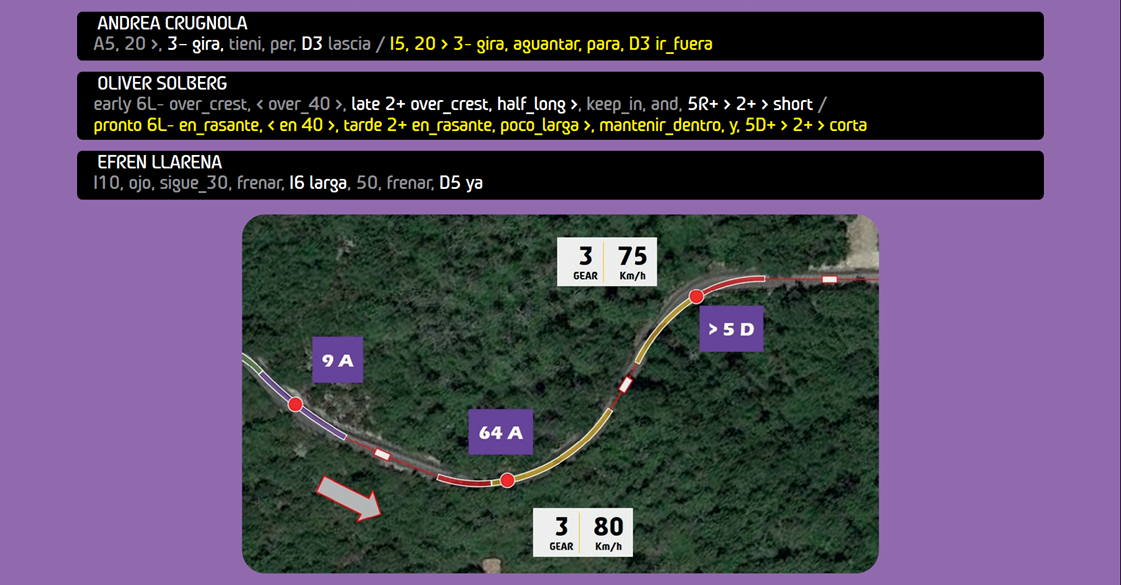

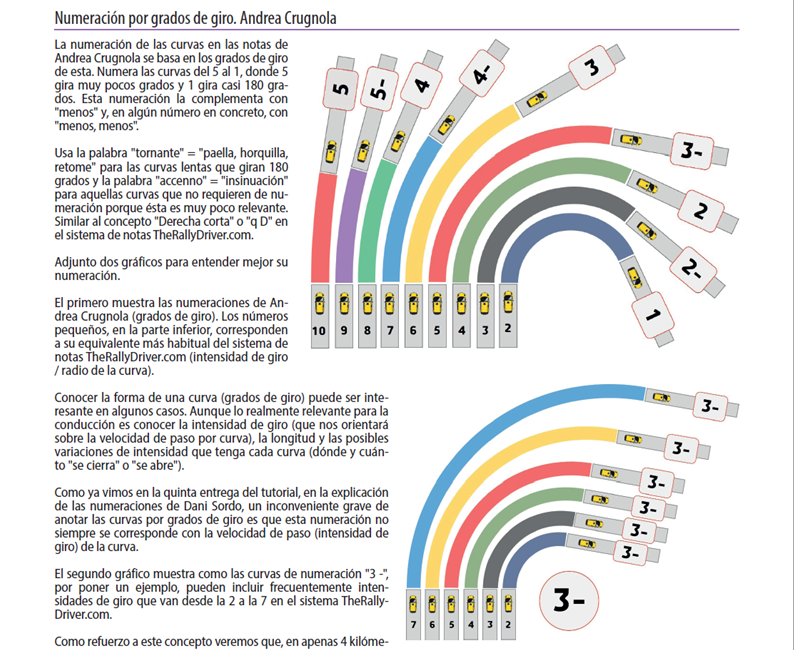

La peculiarità del lavoro di David, che nessun’altro ha ancora proposto al pubblico, è l’analisi dei sistemi di note dei principali attori del WRC, andando a sviscerare e comparare l’un l’altro in specifiche sezioni di PS delle scorse edizioni del Rally RACC in Spagna. Qui sotto un esempio, confezionato dopo l’appuntamento del Rally di Roma Capitale dello scorso anno:

Area di contatto

Il metodo proposto prevede che al pilota vengano fornite le informazioni necessarie per individuare l’area di contatto ottimale ed efficace per ciascuna curva: molti piloti associano questo concetto con quello di traiettoria e dove sia localizzato il punto di corda in essa. La Vittorio Caneva Rally School, che collavora con David, utilizzò per prima questo concetto

L’area di contatto sottintende più di una informazione:

- lunghezza

- variazioni di intensità

- aggiustamenti e

- quando e se sia possibile usare l’esterno e l’interno della curva

La lunghezza conta

La lunghezza della curva è fondamentale: immaginate un tornante di montagna ed una parabolica di un catino americano. Entrambi hanno lo stesso grado, giusto? A far cambiare la velocità di percorrenza è il loro raggio, quindi la loro lunghezza. L’app RallyPacenotesApp permette, tramite un trip (configurabile anche via BlueTooth) di misurare la lunghezza delle curve (oltre che di rettilinei). La nota della curva sarà composta da due cifre, il primo per l’intensità, il secondo per la lunghezza in decine di metri (D45, una destra 4 lunga 50 metri). Ora la PS è descritta in maniera obbiettiva senza lasciar spazio ad approssimazioni: in ciascun tratto cronometrato del rally avremmo lo stesso parametro per decidere che tipo di curva abbiamo di fronte.

Apre e chiude per tutti i gusti

Le variazioni di intensità (aperture e chiusure di curva) vengono suddivise rispettivamente in 3 e 2 categorie.

La chiusura può avvenire:

- nella prima parte della curva (tipo A)

- in mezzo a due curve, da prendere con la stessa traiettoria (tipo B)

- al termine della curva, facendo comparire una controcurva (tipo C)

L’apertura invece tien ìe conto di due fattori:

- se la curva apre non presentando nessuna difficoltà (tipo A), oppure

- se apre non in maniera progressiva per una distanza considerevole (tipo B)

Curiosità: se lo stesso tratto di strada percorso in un senso presenta una chiusura di tipo A o B, nel senso opposto viene descritta con una apertura dello stesso tipo.

Tagliare o non tagliare, questo è il dilemma

Almeno a livello Mondiale, i tagli vengono usati abbondantemente cambiando anche in maniera significativa le condizioni delle PS ad ogni ripetizione delle stesse. Qualora sia possibile il ‘taglio’, occorre indicare ‘quanta’ macchina possiamo far uscire dalla sede stradale.

Allo stesso modo la eventuale possibilità di mettere le ruote all’esterno deve essere indicata; infatti potrebbe trovarsi un pericolo in uscita di curva: qui l’esempio proposto dall’autore, dove Nasser Al-Attiyah con il nostro Giovanni Bernacchini.

I link, il collante tra le curve

Dopo aver passato in rassegna come descrivere i rettilinei, David dedica quasi due volumi per passare in rassegna i cosidetti ‘link‘, sia di quelli tra due curve della stessa direzione che di direzioni opposte. L’autore si sofferma qui a lungo per ‘amalgamare‘ tutti i concetti presentati: in questo caso ci si interroga quando convenga utilizzare i connettori e quando le variazioni di intensità, in base al tipo di curve che abbiamo di fronte ed alla semplicità di lettura e comprensione.

Frenare, dossare con moderazione; ‘chicanare’ con logica

Le rifiniture proposte nella seconda metà del quinto ed ultimo volume si rifanno a come indicare le frenate, i dossi/salti e le chicane artificiali.

Nei primi due casi la raccomandazione principe è quella di non abusare con la segnalazione di pericoli in tutta la PS: più si fa uso di tratti ‘attenzionati’ e più il livello di attenzione su di essi perde di significato, rischiando di farci distrarre dalle vere insidie.

Essendo un sistema di note oggettivo, le distanze in metri la fanno da padrone: sia per capire da che punto iniziare a frenare, sia per localizzare il dosso o il salto. Inoltre, a proposito di ‘jumps‘, l’autore li suddivide come fa per le intensità delle curve, dando un numero in crescendo per segnalare a che velocità possiamo affrontarlo; e propone di classificare i salti in base a che comportamento faranno subire all’aut0, se la farà appena allegerire, se la farà scomporre causa irregolarità della strada o la farà letteralmente volare da terra.

Conclusioni

Giunti ai giudizi finali, queste sono le ie considerazioni:

- L’opera è unica nel suo genere: a David va dato il merito di aver portato alla luce tutti i segreti delle note dei principali attori del Mondiale (tra l’altro è alla ricerca di iniziare a studiare altre lingue di navigatori come finlandese, svedese e norvegese per citarne alcune, quindi il suo lavoro non si fermerà di certo)

- I concetti vengono esposti in maniera chiara e schematica, conditi da disegni e le famose orthomaps dove riporta traiettorie e punti importanti del tratto di PS di volta in volta in considerazione

- Questi concetti sono una formidabile ossatura di un sistema di note per poi personalizzarli a proprio piacimento e nella propria lingua

- L’unica nota ‘limitativa’ è proprio quella linguistica: a meno che non mastichiate un minimo di inglese (o spagnolo) non è così semplice assimilare a fondo i concetti della collana

Let’s face it: we are always fascinated by onboards (or cameracars as we want to call them) and their sounds. We don’t tolerate music covering engine noise, rocks scratching the underbody and the voice of the codriver. We have to feel enraptured by the situation, as if we were strapped to the roll bar in the trunk.

That rain of words, rhythmically in tune with the advancing road for many is pure magic: it takes years of practice and sometimes a few courses to reach the levels of Ingrassia, Gilsoul, Martin, …

Some apps have appeared on the market, such as RallyPacenotes, which have brought the “objective” method of taking pacenotes within everyone’s reach: this concept is the basis of the work of David Nafrìa Mitjans and his series “To see the invisible” (“Ver lo invisible” in the original Spanish language).

The Catalan from Barcelona, born in 1971, starts as a codriver in 1989: on the left seat since 1991, he will collect many victories in Spanish one-make trophies until becoming official driver for Peugeot Sport Spain in 2003. Among the career high points, the podium at Rally Catalunya in the 1997 PWRC. Since 2014, he has been dedicated to one-on-one note courses from his method, TheRallyDriver.com.

The series is on sale on Amazon since January in Cantabrian and Anglo-Saxon languages: it comes with 5 volumes with flexible glossy cover 20.32 x 0.71 x 25.4 cm of about 100 pages each, at a price of about 20€ each.

The peculiarity of David’s work, that no one else has yet proposed to the public, is the analysis of the note systems of the main actors of the WRC, going to dissect and compare each other in specific sections of SS of the past editions of the RACC Rally in Spain. Here below an example, extracted after last year’s Rally di Roma Capitale:

Contact area

The proposed method requires that the driver is ‘fed’ with the necessary information to identify the optimal and effective contact area for each curve: many drivers associate this concept with that of trajectory and where the apex is located in it. Vittorio Caneva Rally School, which works with David, was the first to use this concept.

The contact area implies more than one piece of information:

- length

- intensity variations

- adjustments and

- when and if it is possible to use the outside and the inside of the curve

Length matters

The length of the curve is fundamental: imagine a mountain hairpin and a parabolic curve of Indianapolis. Both have the same degree, right? What makes the speed change is their radius, hence their length. The RallyPacenotesApp allows, through a trip (also configurable via BlueTooth) to measure the length of the curves (as well as straights). The curve note will consist of two digits, the first for the intensity, the second for the length in tens of meters (R45, a rightwith intensity 4 and 50 meters long). Now the SS is described in an objective way without leaving room for approximations: in each timed section of the rally we would have the same parameter to decide what kind of turn we have in front of us.

Openings and closings for all tastes

The intensity variations (turn openings and closings) are divided into 3 and 2 categories respectively.

The closure can occur

- in the first part of the curve (type A)

- in the middle of two curves, to be taken with the same trajectory (type B)

- at the end of the curve, making a counter-curve appear (type C)

The opening instead takes into account two factors:

- if the curve opens without any difficulty (type A), or

- if it opens not in a progressive way for a considerable distance (type B).

Curiosity: if the same stretch of road traveled in one direction has a closure of type A or B, in the opposite direction is described with an opening of the same type.

To cut or not to cut, this is the dilemma

At least at the WRC, cuts are used extensively, changing significantly the conditions of the stage at each repetition of the same. If it is possible to ‘cut’, it is necessary to indicate with ‘how much‘ car we can leave the roadway.

Similarly, the possibility of putting the wheels outside must be indicated; in fact, there could be a danger in the exit of a curve: here is the example proposed by the author, where Nasser Al-Attiyah with Giovanni Bernacchini.

Links, the glue between curves

After reviewing how to describe straights, David devotes almost two volumes to review the so-called ‘links‘, both those between two turns of the same direction and those of opposite directions. The author pauses here for a long time to ‘amalgamate’ all the concepts presented: in this case we ask ourselves when it is convenient to use the connectors and when the intensity variations, according to the type of curve we have in front of us and the simplicity of reading and understanding.

Brake, jump with moderation; ‘slaloming’ with logic

The refinements proposed in the second half of the fifth and final volume refer to how to indicate braking, bumps/jumps and artificial chicanes.

In the first two cases, the main recommendation is not to overdo it with the signalling of dangers throughout the SS: the more you make use of ‘warned’ sections, the more the level of attention on them loses meaning, risking distracting us from the real traps.

Being an objective note system, distances in meters are the pivot theme: both to understand from which point to start braking, and to locate the bump or the jump. Moreover, about jumps, the author divides them as he does for the intensity of the curves, giving a number to signal at what speed we can face it; and he proposes to classify the jumps according to what behavior they will make the car undergo, if they will just make it lighter, if they will make it decompose because of road irregularities or they will literally make it fly off the ground.

Conclusions

Arrived at the final judgments, these are the considerations:

- The work is unique in its kind: David should be given credit for bringing to light all the secrets of the notes of the major drivers in the WRC (among other things, he is looking to start studying other languages of navigators such as Finnish, Swedish and Norwegian to name a few, so his work will certainly not stop)

- The concepts are exposed in a clear and schematic way, filled with drawings and the famous orthomaps where he reports trajectories and important points of the SS stretch

- These concepts are a formidable framework for a system of notes that can then be customized at will and in one’s own language

- The only ‘limiting’ note is the linguistic one: if not well skilled in English (or Spanish) it is not so easy to assimilate the concepts of the series.